Developing Empathy from International Economics

Reflecting upon a semester abroad studying political and economic systems in Shanghai, China.

Unknown Adventure Awaits

“Why are you going?” they asked. Friends and family peppered me incessantly with questions regarding the purpose of my expedition. I failed to give them a straight answer, and they knew it. At the time, it was a feeling that I could not explain to myself - let alone the outside world. Something drew me in towards China, but I struggled to put this captivation into words. In hindsight, it is clear why I went. I was enamored by the intersection of economics and politics. Forget that I didn’t know a lick of Chinese when I first arrived. I needed to be there; to experience the everyday life of what it meant to be a Chinese citizen; to better understand government’s role in people’s everyday life; to understand how this new become powerhouse economy has and has not benefited her people. I elected to study abroad in Shanghai, China for four months in Fall 2017, and what I learned from my macroeconomics professor about the political economy of China has been nothing short of remarkable.

In the late 1970’s, the Chinese government implemented reforms that transitioned the country from a planned economy towards a free-market. It was as if someone had stored decades worth of economic potential behind the gates of a dam. Bit by bit, politicians experimented with poking holes within the dam’s walls to see where the water would flow and at what speeds. Slowly, not all at once, the dam began to be deconstructed. Money has flown fervently to certain areas of the country; so much so that, according to The Guardian, the country has lifted half of a billion people out of poverty in the past decade. Yet, not all of the valley beneath the dam has received its fair share of prosperity. Coupled with mass poverty alleviation are questions of morals and ethics.

China has reaped the benefits of capitalism such as massive GDP growth and increased economic efficiency, but symptoms of capitalism such as increasing income inequality and unequal wealth distribution have followed suit. The government now finds itself facing the issue of balancing economic efficiency while maintaining equality. Upon further examination of current income and wealth gaps among the Chinese citizenry, we will diagnose root causes of these disparities such as the outdated hukuo system, corrupt privatization of land, and unfair rural land ownership laws in an effort to better understand potential solutions.

Sunset captured from the Shanghai tower. At 2,073ft, the building is the 2nd tallest in the world.

A Brief History of China’s Economic Reform/Resurgence

Since the inception of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and up until the late 1970’s, China had a command economy - a system where the central government made all of the decisions. During this period of time, Chairman Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CPC) implemented economic practices based upon self-sufficiency by limiting the number of trading partners that the country did business with. After the passing of Chairman Mao, this policy changed under the leadership of General Secretary Deng Xiaoping in 1978. Deng Xiaoping introduced characteristics of a free-market - a system that lets the laws of supply and demand determine production and price with little government control – under what became known as the “open door policy” in China. Free market reform began with the decentralization of agricultural commune systems in the rural countryside under the household responsibility system.

My macroeconomics professor grew up on one of these communes. His personal anecdotes were what I had unknowingly longed for when I made the decision to study in China. With a PhD in economics, he advises the Shanghai government on policy measures and taught on the side to supplement his income. Under the commune system, he served on a production team to produce shoe laces. He had to hit quotas to ensure that his commune leader would not reprimand him. There was an unspoken rule among his family members. His parents and cousins all knew that they had to give middle-of-the-road effort – neither minimal nor maximum. Minimum effort resulted in a failure to meet quotas. It showed that you were lazy, and you could face harsh consequences to be made an example of. Maximum efforts were rarely rewarded. They simply raised the expectations of the commune leader. If you produced more shoe laces one week, you would be expected to sustain this output. There was not an incentive to work hard. There was an incentive to be mediocre.

Open-door policy reformed communes. Production teams now allowed farmers to share a portion of the outputs. After incentivizing work, production teams began to see farmers put in more effort thus increasing the efficiency of the agricultural economy. A study featured in the academic journal Economic Development and Cultural Change found that grain output increased from 305 million to 407 million tons in just six years from 1978-1984. The impressive growth resulting from the free market soon became undeniable, and government officials began to ramp up their reform measures. Legislative efforts to create a free market economy spread across nearly every industry and region of the country.

My professor stood by and watched his loved ones become more prosperous on the farm. The affluence he and others experienced only made them more ambitious. Granted, he wasn’t a man that fancied the glamor or business of a city. He instead had an appreciation for the countryside – where he had gained his roots. Yet, the reason he moved to Shanghai was one of the initial inequalities I came to identify when I was in China – the urban-rural divide. If you wanted a better life, you made your way to the city. With the reform of the commune system, Chinese citizens were now free to move about the country freely for the first time under the CPC’s rule. They were free to travel towards the best opportunity that they could fine. The biggest migration in all of man’s history was soon underway; Chinese citizens completed a mass exodus from the countryside to the city in search of work.

The bulk of the economic potential that had been released was in manufacturing industries. The wages that Chinese urban-dwellers now received due to reform was a vast pay raise relative to what little they had received previously. Yet, in comparison to the rest of the world, China’s labor costs were dirt cheap. With wages low, manufacturers could diminish their input costs immensely by producing goods in China. China quickly became an industrial powerhouse of export goods for buyers across the globe. According to an analysis performed by China & World Economy, exports grew at an average of 16.7 percent year-over-year from 1978-1997. As exports left the country, foreign investment and new technologies began to flood in resulting in a surge of the nation’s gross domestic product – a figure representing the total services and goods produced by a country in a given year. The GDP growth rate – a measure of how quickly economic output was flowing – doubled overnight after reform. Today, according to the World Bank, China possesses the world’s second largest economy worth 11.2 trillion USD. China has emerged from an underprivileged and underrepresented nation to a developing country that holds a major stake in the world economy today. Yet, not everyone in China has received his or her share of the economic success.

The Shanghai Tower looming in the background offers an interesting contrast in architecture to this traditionally designed building.

Income Disparity Rising Due to “Hukuo” System

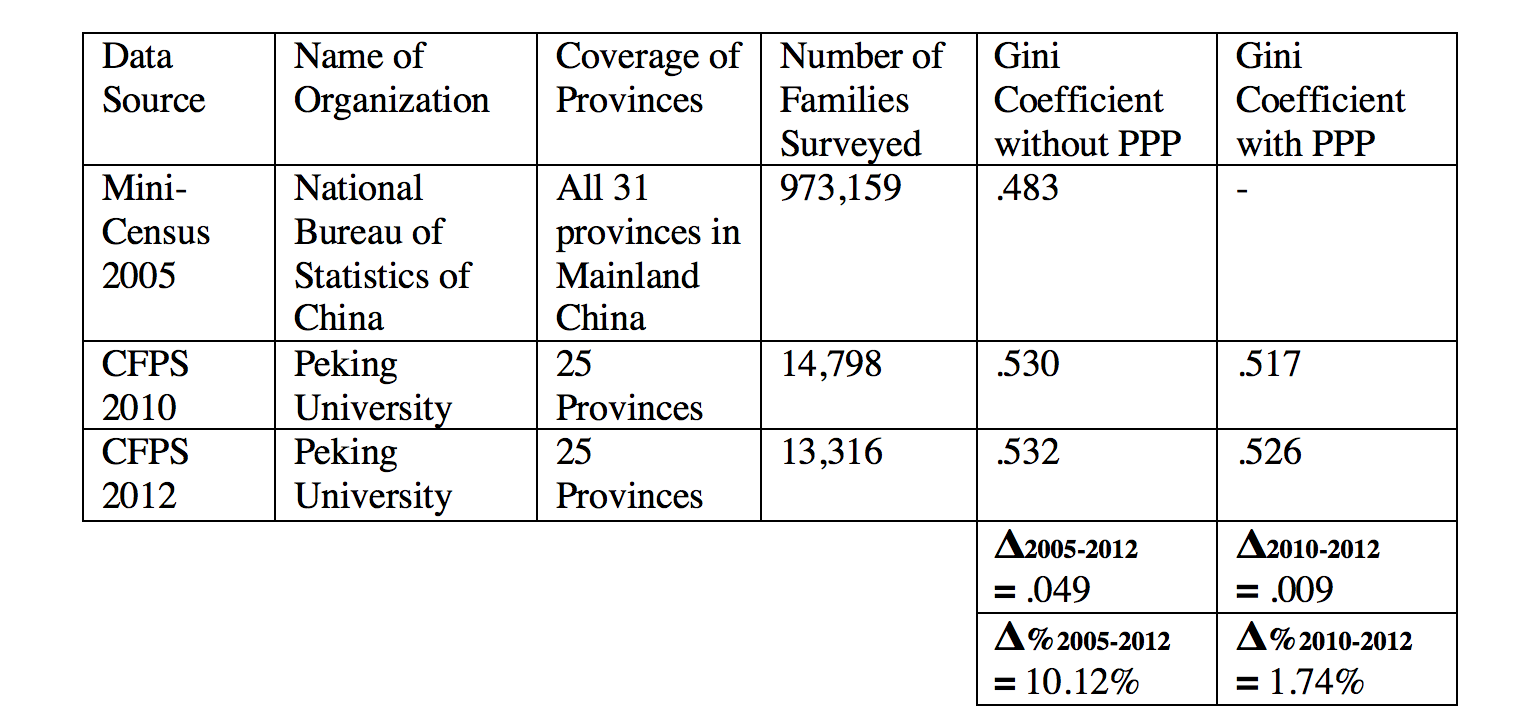

As China’s economy has grown, so has its income inequality. Peking University completed a survey on household incomes in 2010 called the China Family Panel Studies or CFPS. The CFPS spanned 25 provinces and 14,798 families in Mainland China (excluding Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, Hainan, Ningxia, and Qinghai). The university utilized the data on household income to calculate a nationwide Gini coefficient – a measure of income disparity with 0 representing perfect equality and 1.00 representing perfect inequality. The CFPS 2010 survey yielded one raw Gini coefficient and one adjusted coefficient with consideration to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) – a method of evaluating expenses based upon the regional cost of a common basket of goods. PPP allows for more accurate cross-referencing in urban and rural regions with respect to cost of living. Peking University then followed the exact same procedures they had implemented in CFPS 2010 and conducted this same survey again in 2012. The results of both of these studies along with a government study from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Mini-Census 2005, CFPS 2010, CFPS 2012 Data. The National Bureau of Statistics of China did not provide a Gini coefficient adjusted for PPP; therefore, this data is unavailable.

Δ%2005-2012 shows that inequality grew by 10.12% in seven years – a clear indicator of an upward trend in income inequality. Δ%2010-2012 has been adjusted for PPP and corroborates the fact that the Gini coefficient continues to grow, but the growth was much smaller. This could be potentially an indicator that the rate of inequality growth is beginning to slow down. Due to the information in Table 1, modern economists contend that China is nearing a turning point where inequality will begin to decline based upon the Kuznets Curve. My professor is unsure of this hypothesis. He’s a man whose pride for his nation is neither resounding nor absent. It’s careful. In a country without the right to speak freely, he quietly challenges what he hears. He yearns for the prosperity of all people in his country, but he does not believe the path to success is wishful thinking. Instead, he relies on empirical data. To him, politicians lie but numbers do not. Then again, what can he make of numbers when the politicians control them? Here lies the tricky balance of being a Chinese economist. You must always be sensitive to whom you are talking to and what you are talking about. Should you have a dissenting opinion from the CCP’s political machine, move forward with caution.

Our class reviewed the Kuznet’s curve. Continued growth will reach a turning point in which income will fall. This hypothesis follows an inverted U curve as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Kuznets Curve. Countries grow simultaneously grow income and inequality until a “turning point” is reached; at this point, income growth will continue while inequality will fall.

Rudimentary economies begin on the left and progress up the curve through industrialization - producing basic materials, commodities, and basic manufacturing. At a certain point known as the “turning point income,” inequality begins to taper and a developed economy emerges made up of advanced manufacturing, consumer goods, and consumer services. Some Chinese economists believe China’s “turning point” will be, in part, the completion of the mass-urbanization of rural immigrants. According to Yale Insights, 1950, just 13% of the Chinese population lived in cities; by 2010, 45% of Chinese citizens lived in urban areas, and this figure is expected to grow to 60% by 2030. The theory is that, at a certain point, enough Chinese citizens will live in areas of higher opportunity that the scales of income inequality will begin to fall.

Provinces on the Eastern Coast of China such as Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Jiangsu each possess a GDP per capita of 10,000 USD or higher while western, rural provinces like Tibet, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan each possess a GDP per capita under 6,000 USD. Chinese citizens residing in the countryside have seen their earning power continue to falter relative to their counterparts living in cities. According to an article in The Economist, the average urban income was 3.3 times higher than the average rural income in 2009; this figure fell to 2.7 in 2015. On the surface, this seems to indicate progress towards more equitable geographic earning potential.

My professor believes otherwise. According to him, a more in-depth look indicates that this data is skewed due to the “hukuo” system. The hukuo system is similar to an urban passport; it was implemented in 1954 as a way of restricting travel for China’s large rural population and preventing citizens from challenging Chairman Mao. This system was designed as a method of control to stop rural citizens from changing their legal residence. Today, a high volume of people from the countryside continue to flock to urban areas for better paying jobs. While they may reside in cities for long periods of time, rural citizens are incapable of changing their hukuo. Thus, rural immigrants who live and work in cities with better paying salaries are skewing average rural income data upward because they are still legally classified as rural residents.

In addition to skewing data, hukuo has contributed to the increase and perpetuity of inequality among rural citizens. Those with an urban hukuo have access to better public goods – better healthcare, education, housing, and pensions - than those with a rural hukuo. These public goods are segregated between rural and urban peoples. For instance, rural citizens who immigrate with their children to urban areas have to send their children to special immigrant schools. There are 500,000 immigrant students in Shanghai alone but only 145 eligible schools for these students to attend. These schools are largely overwhelmed, underfunded, understaffed, and generally have less resources than urban schools.

When I left the Shanghai city-limits, the urban-rural divide became tangible. I no longer watched the teenage sons and daughter of overnight Chinese billionaires race their foreign cars through the streets of Shanghai. Instead, I saw modest school structures and humble beginnings – a lack of resources but not a lack of hope. The teachers’ kindness and sincerity radiated a warm light towards their students, but this light was seemingly outshined by the glamor of the big city. It was a town and school propped up within the past decade to care for the immigrant children of working class people. Their parents worked in the city but could not afford to live there. They simply wanted to give their children a better life – a sort of Chinese take on what I had come to know as the American dream.

Yet, the conditions of education in China are the exact opposite of America. Schools in urban, American cities often struggle the most in sustaining the necessary resources to deliver a valuable education while suburban schools thrive. In China, students in urban school systems receive a much higher quality education than their suburban or rural counterparts. This disparity in education accelerates the pervasive cycle of income inequality and the urban-rural divide.

Plus, due to hukuo, rural immigrants often have to travel back to their home village for healthcare services. In the event of a medical emergency, individuals may have to travel across the country to receive proper medical attention. Along with the cost of tickets, the patient’s maladies may become worse as they wait to receive medical attention. This prolonged delay to see a doctor can translate into an increase in medical costs if the problem gets worse. Hukuo also leaves rural immigrants without a pension like their urban counterparts. Urban citizens utilize pensions to guarantee their financial security, enjoy a better lifestyle during retirement, and even pass along wealth to their family. Rural citizens are left without these luxuries.

Folks enjoy the remaining pieces of dusk on East China Normal University's campus as a statue of Chairman Mao looks on.

Wealth Gap Increasing Based Upon Proximity to Power

Privatization of the Chinese economy has also resulted in vast increases in wealth depending on individuals’ proximity to power – both in geography and relationships. According to a journal published by the Australian National University Press, individuals in urban areas experienced an average of 18.9 percent growth from 1995-2002. Individuals in rural areas during the same time period experienced an average of 1.9 percent growth in their wealth, per annum. This can largely be attributed to the privatization of land. As a part of their economic reforms, the Chinese government began to sell public land to private individuals for amounts well under market value. Individuals who possessed “guanxi” - connections or relationships - with those in the public sector, such as provincial leaders, were more likely to gain access to the sale of the land. So, while public lands were being privatized, it was not done so in a truly free market because not all buyers possessed the powerful connections to gain access to the sale.

My professor didn’t have access to the sales of Shanghai real estate back in the 1990’s, but his brother did. His brother was an art curator in downtown Shanghai. He also occasionally served as a dealer of high value pieces of work. Politicians would come to him to purchase sculptures and paintings, but they never paid in cash. They’d use their guanxi to look out for my professor's brother when an opportunity for financial gain presented itself. For instance, when a Shanghai high-rise that was previously owned by the government went on the market, my professor's brother gained admittance to the sale. Politicians formed a buying group made up of the people whom they owed favors. The high-rise was sold well below market-value and transformed into apartments for urban city dwellers. The curator gained access to more than just the sale of the high rise. He soon held stakes in old office buildings, manufacturing facilities, and restaurants. Suddenly, an art curator with no background in real estate, rose to the level of the Shanghai elite as a real estate mogul.

At this time, China had not yet developed a de jure real estate market because land belonged to everyone in the country and could not be bought or sold. In reality, a de facto real estate market run on guanxi and graft was illegally functioning during this time. The result of these measures is that high performing real estate assets, particularly in urban areas, have been concentrated in the hands of the wealthy and the well connected. It is also important to note that government officials who sold public lands under market value sacrificed potential government revenues that could have become investments in future public goods. Public goods such as pension coverage, infrastructure, education, housing, or health care could help alleviate large gaps in wealth. Instead, government officials have robbed their own people of the chance to redistribute wealth at the expense of increasing their own.

The real estate market is also dysfunctional in rural areas but for different reasons. China’s massive population requires a high number of farmers to remain within rural areas. Yet, farmers want to flock to sell their land and flock to cities for better opportunities. To prevent farmers from moving, modern real estate barriers in rural areas have been built up to inhibit citizens in the countryside from building their wealth. Rural peasants can’t sell their land at market prices which has made many hesitant to leave their plots of land. In towns such as Xiaogang, families were given plots of land to farm as a part of the household responsibility system. The families are accountable for the output of the land, and they’ve lived on it all of their life. Yet, they were never given legal ownership of the land even after the household responsibility system was reformed. For instance, in 2014, a group of Xiaogang farmers tried to purchase a small plot of land to rebuild a shrine dedicated to the earth god that was destroyed by the communists in the 1950s. This land purchase would have been the first in 67 years in Xiogang. Instead, the local government denied the transaction and the potential buyers were fined for trying to operate within the real estate market. Rural citizens feel trapped in an endless cycle. They cannot access the equity within the land that they farm, nor do they feel that they can abandon their land for better opportunity in urban areas. These peasants are left to watch others’ fortunes grow while they suffer. This is an intentional trap implemented by local governments to ensure there are farmers producing food.

Two luxury car companies - Mclaren and Lamorghini - had dealerships at the base of the office building where I completed an internship.

The Political Implications of China’s Growing Inequalities

A 1993 New York Times article stated that China’s de facto real estate market “says less about market economies and more about corruption.” Within this description of the shady tactics used in land deals lies a complex problem that China still faces today. The Chinese government describes its economy as a socialist system “with Chinese characteristics,” but the disproportion in wealth and income coupled with inequitable, corruptive tactics hardly display efforts of becoming a socialist society - nor is this reminiscent of an open, fair market. This is where the government officials find themselves at a crossroads; their political and economic ideologies clash with one another. The CCP is interested in continuing open market policies and scaling the economy, but they want to maintain the image of a socialist government that is for the masses in order to preserve their own power and legitimacy.

My professor is at the crossroads himself. As an economist, he knows that capitalism results in more output. Yet, he’s worried that the rising tide of money will not lift all boats due to the Chinese nature of business. Chinese business practices and standards are not based upon morals and ethics. They’re based upon shame, and what you can get away with. If you can exploit an opportunity without getting caught, you are fool not to. My professor is both related to and acquainted with people who have implemented his policy recommendations but found loopholes within them to game the system. His friends and family have gotten wealthy, but he hasn’t. His moral compass has steered him away from playing politics, but will other Chinese businessmen adopt similar ethical standards? Frankly, I doubt it. The only way Chinese business culture will transform is if the CPC is pressured to implement such changes.

Consider General Secretary Deng Xiaoping’s aforementioned decision in 1978 to experiment with free-market measures in the agricultural industry. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), incentives to produce agricultural goods were removed entirely and the economy became increasingly inefficient. China struggled to pay farmers and, worse yet, feed their own people. Per capita income in 1978 was 285 Yuan – below the poverty line standards of both the Chinese government and the World Bank. General Secretary Deng Xiaoping knew that reform was not only necessary for the people but also necessary for the survival of the party. History is often our best teacher, and I think this case is no different. The modern-day CPC will not seek drastic reform measures until inequality becomes an issue of social stability and party survival.

The head of the NBS, Ma Jiantang, was the first central government official to declare income inequality as a problem when speaking to the press in 2013. He stated that the “curve of Gini coefficient demonstrates the urgency for our country to speed up reform of the income distribution system to narrow the poor-rich gap.” Though this was encouraging, no serious legislative measures followed suit. This was perhaps an indication that the political pressures were not yet large enough for the government to take action. Four years later, General Secretary Xi Jinping of the CPC acknowledged the problem at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. On October 24th, 2017, Xi Jinping stated the following: “The principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved and is now that between the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life and unbalanced and inadequate development; it reflects the realities of the development of Chinese society.” Xi Jinping, the head of state, speaking before his legislative body is a much more promising indication that reforms are on the way.

A guard standing post outside of Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

Potential Solutions for Reducing Income & Wealth Inequality

The party can no longer ignore the imbalances that exist within their society because, similar to 1978, the current economic practices represent a threat to the party’s legitimacy. Given the need for reform, I propose the following solutions that can alleviate income inequality and political pressure while encouraging economic efficiency:

- Income inequality is being propped up by the remnants of the outdated hukuo system. The concept of an urban passport was supposed to maintain political stability during Chairman Mao Zedong’s time in power. Today, the system is contributing to the increase of inequality and instability. A country that adopts free-market practices and seeks to develop a modern economy cannot restrict their own people from moving freely within the country – especially with consideration to modern-day technology. Chinese citizens can connect virtually and communicate with other parts of the country. There is not a firewall that can prevent rural citizens from seeing or hearing accounts of the urban success. A refusal to end the inequitable hukuo system could result in political instability. Plus, China should see be able to identify the massive opportunity cost of refusing to unleash the economic potential of rural populations. If citizens were allowed to resettle within their own country freely, they could uncover better opportunities matched to their skillsets. This could result in better paying jobs and a more efficient economy. The country introduced hukuo reform measures in 2013, but the measures did not necessarily solve issues of stability in rural regions. Instead, reform called for increased mass urbanization of 400 million people at the cost of 40 trillion Yuan or 6.4 trillion USD. The legislation seeks to alleviate the hukuo problem by continuing to bolster opportunity in urban areas, but it still does not remove barriers for rural immigrants to gain urban hukuo permits. Hukuo needs to be reformed and replaced on a much wider scale. To do this, the government would need to invest in the infrastructure within their cities. No longer should students be segregated by school – no longer should patients be segregated by hospital; instead, the government must invest money into the infrastructure found in cities so that all Chinese citizens, no matter their background, can access quality public goods. By investing resources and improving this infrastructure, the government can temporarily employ more people to complete these projects. This can benefit the economy in the short term, but the long-term implications would be substantial. Rural citizens could more freely move throughout the country based upon opportunity thus creating a more adept workforce. The result would be a more efficient skills-based economy with better paying jobs, decreased income inequalities, less regionally based discrimination, and less political pressure on the CPC.

- In addition to easing income inequalities, China must also begin to redistribute wealth. Bureaucrats from the 1990’s in China unfairly benefited from the privatization of land. To alleviate the disparity in wealth, China should implement a property tax. A property tax is calculated according to the value of the land after an appraisal is performed. The tax is then levied as a portion of the land value. This type of tax is paid to the government yearly in an escrow account. Developed countries around the globe utilize the property tax as a mechanism to pay for public goods such as healthcare and education. Currently in China, there is no holding cost for owning property. This means that wealthy individuals who were granted access to the illegal real estate market in the 90’s have been able to sit on the land at no expense while their wealth accumulates. Properties have been untaxed and therefore underutilized. In fact, according to a CNBC article, there were 1.33 million square meters of vacant residential space in Beijing’s Chaoyang district in 2013. While urban area property prices have surged, some buildings have remained completely unoccupied. Implementing a property tax could ensure a more equitable and efficient real estate market and help solve wealth inequality. Property owners would either sell the land to get out of paying the tax or begin to utilize it to generate a revenue stream to pay for the tax. Either way, it would level the real estate playing field. Not to mention, comprehensive tax reform such as this could help pay for the public infrastructure investment that I proposed when previously discussing hukuo reform.

- China must also pursue rural land ownership reform. Under the household responsibility system, plots of land were divided and given to families. The families were accountable for the output of the land – much like capitalism – but the families are unable to claim ownership of this land even today. This is an old method of control from the days of Chairman Mao Zedong. The CPC must recognize that such tactics cannot function in a free-market. As mentioned previously, it is a contradiction of ideologies and could result in social upheaval. Plus, the absence of a functioning real estate market in these countryside provinces inhibits rural residents’ ability to invest money and build wealth. The country must privatize the land in the west in a fair and equitable fashion – unlike that of urban properties in the 1990’s. By doing so, the government will be allowing people the means to provide for themselves thus alleviating some of the burden of government’s responsibility to provide public goods.

The Shanghai skyline at night.

Factors of Consideration Regarding the NBS & Poverty Alleviation

The government is aware of increasing inequalities among their citizenry, but they do not release reliable data on the issue. China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) stopped releasing the Gini coefficient after it reached .483 in 2005 due to “gray income.” Gray income is the underreporting of income on tax forms and government surveys. This leaves the NBS without reliable data to calculate the real Gini coefficient. The practice of underreporting gray income has reportedly increased since Xi Jinping has taken office. There are no clear statistics to back this up given the illegal nature of the matter, but many rich Chinese people have refrained from flashing their wealth ostentatiously since Xi Jinping declared that he would go after both the “tigers and flies” that plague the government with corruption. Due to gray income, the data for Gini coefficients utilized in this paper is derived from Peking University as seen in Table 1.

While most metrics do indicate rising inequalities in Chinese society, it is also important to note the data that indicates the progress China has made. Since the 1980’s, has alleviated more people out of poverty than anywhere else in the world. Yes, inequality has increased, but the fact remains that China has pulled nearly half of a billion people above the World Bank’s poverty line in only three decades. The mass alleviation of poverty can be attributed to free-market measures that have improved China’s economic efficiency.

Shot of the Chinese countryside from the highway.

Approaching Inequality with Empathy

So, the question becomes, have the ends justified the means? Have the CPC’s reform measures to create a more efficient economy paid off? It’s too early to tell. Certainly, raising nearly half of a billion people out of poverty is no easy feat; however, the inequalities that have resulted from the matter could produce political instability. Then again, the CPC has historically chosen to take necessary legislative actions just before a threat escalates to the level of political instability. Perhaps inequality does have to continue to increase for the party to take notice and, henceforth, take firm action against the issue. The most recent comments from General Secretary Xi Jinping certainly indicate an acknowledgement of the problem, but the lack of decisive reform shows that he is merely wading the waters of reform and not yet diving in.

Moving forward, I believe that my three proposed solutions - hukuo reform, property tax implementation, and rural land ownership reform – could appeal to the CPC because they can mitigate inequality while raising economic efficiency. One cannot ignore the political implications, however, as this would require the CPC to give up two of their effective methods of control in hukuo and rural land ownership. In addition, implementing a property tax would negatively impact bureaucrats who engaged in the corrupt real estate market in the 1990’s. The reality is that many of these corrupt officials are still in office today, so support may be hard to come by for this reform. Looking forward to the future, I do predict that the continuation of mass-urbanization will push China along the Kuznets’ curve but that the turning point will not be reached until policy is implemented to ease the urban-rural divide. However, it is up to the CPC and the amount of political pressure they feel to decide whether or not they will take legislative action in helping China reach the turning point faster.

There is another key factor of consideration that has not yet been addressed in this paper - inequality in my home country, the United States of America. I used this piece solely as an opportunity to analyze the 5 months that I spent in the People's Republic of China. This is not to say that America does not currently face it's own economic challenges. While the prescribed legislative action to each individual country may differ, the two world powers are united in that they both are increasingly experiencing the symptoms of rising inequality. The culture, languages, and traditions are different, but one thing is the same - people are just trying to get by. Most citizens in the US are focused not on pontificating upon broad macroeconomic policy but rather providing for their families and serving their local communities. The same is true in China. Most folks are just trying to get by. Domestic and international media has us incessantly searching for reasons why the two world powers should be at odds, when in reality the folks making decisions in DC and Beijing are just a fraction of each country's representative populations. There are more people just trying to get by than there are actively fighting economic and cyber skirmishes. I do not seek to gloss over the well documented geopolitical conflict between the two nations. Rather, I am just saying that if you put an American citizen and a Chinese citizen in a room and remove the language barrier, the two people would find more similarities than differences, more humanity than politics, and more empathy than disdain.

It is easy to get lost in the ramifications for individuals when discussing broad policy measures - easy to forget that the goal of said policy is to serve the citizen. Perspectives from people like my professor are necessary to bring humanity to generalized systems, policies, and practices. At the time, my decision to study abroad in Shanghai was unclear to me. I now know that my professor's story is the reason I went to China. Granted, I didn’t know that I would meet my professor specifically, but I knew that I would have the opportunity to hear someone’s story. The textbook ideas, concepts, theories, and perspectives that I have learned throughout my college career have been educational but distant. There was nothing tangible about the lessons. I could not grab hold of what I was learning. My professor’s story was different. He taught me the history of policies, then discussed his personal interaction with them. Our one-on-one conversations are forever cemented in my mind. He taught me about more than just Chinese economic reforms. He taught me how to empathize with a person who has experienced circumstances nearly incomprehensible to that of which I had ever known. The ability to empathize is a skill that I will take forward throughout the rest of my professional career, and I hope it’s a skill that both the United States' and China’s wealthy/connected elite will take into consideration when seeking a solution to rising income and wealth inequalities in their individual countries.

Enjoying tea with some friends.

More Photos from My Time in China

Works Cited

“About Migrant Schools.” Stepping Stones, steppingstoneschina.net/shanghai-volunteer-english-

teaching-program/about-migrant-schools.

Auffhammer, Maximilian, and Catherine D. Wolfram. “Powering up China: Income Distributions

and Residential Electricity Consumption.” The American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 5,

2014, pp. 575–580. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42921001.

Forsythe, Michael. “Database Tracks ‘Tigers and Flies’ Caught in Xi Jinping’s Corruption

Crackdown.” The New York Times Online, The New York Times, 21 Jan. 2016,

www.nytimes.com/2016/01/22/world/asia/china-database-tigers-and-flies-xi-jinping.html.

Fulda, Andreas. Outdated ‘Urban Passports’ Still Rule the Lives of China’s Rural Citizens.

Independent, 13 Jan. 2017, www.independent.co.uk/news/world/politics/outdated-urban-

passports-still-rule-the-lives-of-china-s-rural-citizens-a7517181.html.

Gopalakrishnan, Raju. “China Eyes Residence Permits to Replace Divisive Hukou

System.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 6 Mar. 2013, www.reuters.com/article/us-china-

parliament-urbanisation/china-eyes-residence-permits-to-replace-divisive-hukou-system-

idUSBRE92509020130306.

Hornby;, Lucy. “China Lets Gini out of the Bottle; Wide Wealth Gap.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters,

18 Jan. 2013, www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-income-gap/china-lets-gini-out-of-the-bottle-wide-wealth-gap-idUSBRE90H06L20130118.

Hsu, Sara. “High Income Inequality Still Festering In China.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 18 Nov.

2016.

Huan, Guocang. “CHINA'S OPEN DOOR POLICY, 1978-1984.” Journal of International Affairs,

vol. 39, no. 2, 1986, pp. 1–18. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24356571.

“Inequality in China.” The Economist Magazine, The Economist Online, 14 May

2016, www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21698674-rising-rural-incomes-

are-making-china-more-equal-up-farm.

Morrison, Wayne M. “China's Economic Conditions.” CRS Briefing for Congress, 6 Jan. 2006, pp.

1–17.

Neville, Edwin L. “The Historian.” The Historian, vol. 58, no. 2, 1996, pp. 422–423. JSTOR,

JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24452317.

“Rich Province, Poor Province.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 1 Oct. 2016,

www.economist.com/news/china/21707964-government-struggling-spread-wealth-more-

evenly-rich-province-poor-province.

Seto, Karen C. “What Should We Understand about Urbanization in China?” Yale Insights, 21 Nov.

2016, insights.som.yale.edu/insights/what-should-we-understand-about-urbanization-in-

china.

Shaffer, Leslie. “Why China Needs a National Property Tax.” CNBC, CNBC, 6 Mar. 2014,

www.cnbc.com/2014/03/06/why-china-needs-a-national-property-tax.html.

Shi, Li. “Changing Income Distribution in China.” China: Twenty Years of Economic Reform, edited

by Ross Garnaut and Ligang Song, ANU Press, 2012, pp. 169–184. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24hcx9.13.

Shi, Li et al. “Empirical Analysis of Wealth Distribution Disparity of Chinese Residents and Its

Changes.” China & World Economy 6 (2005): 40-50.

Stuart, Elizabeth. “China Has Almost Wiped out Urban Poverty. Now It Must Tackle

Inequality.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Aug. 2015,

www.theguardian.com/business/economics-blog/2015/aug/19/china-poverty-inequality-

development-goals.

“World Bank Data Catalog.” Databank - China, data.worldbank.org/country/china?view=chart.

Wudunn, Sheryl. “China Sells Off Public Land to the Well Connected.” The New York Times, The

New York Times, 7 May 1993, www.nytimes.com/1993/05/08/world/china-sells-off-public-

land-to-the-well-connected.html?pagewanted=all.

Yao, Shujie. “Economic Development and Poverty Reduction in China over 20 Years of

Reforms.” Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 48, no. 3, 2000, pp. 447–

474. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/452606.

Xie, Yu, and Xiang Zhou. “Income Inequality in Today's China.” Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 111, no. 19, 2014, pp. 6928–

6933. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23772700.